Hike #1561: 7/23/23 Oldtown to Cumberland MD with Evan "Joe Millionaire" Van Rossum and Everen

This next hike was something I'd been yearning to do for a very long time, and part of a series I'd been looking to do probably over 7 years at this point.

The amazing and continuous trail from Pittsburgh to Washington DC, the combination of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and the Great Allegheny Passage, has looked so tempting to me for so many years, and I decided I would end up doing it as part of the 911 National Memorial Trail after I completed my Perimeter of New Jersey series.

The plans on this, like so many other things, have changed so drastically, and so has my view of the entire thing honestly.

When I started the series, I had tons of support, and groups were big. The planners were all on board to help promote, and it seemed like the next great thing for me to do to stay relevant in the hiking world following the NJ Perimeter, which got me quite a lot of notoriety.

I almost immediately lost some support through my criticism over the route.

David Brickley, who proposed the trail, was always willing to listen to reason when it came to where the route should go. It just had to go from New York City, to the Flight 93 Memorial in Shanksville PA, down to Washington DC, and back to Manhattan. There was already a great amount of trail in place.

However, as this took shape, I felt like the entire trail plan was hijacked by cyclists and they were planning on-road routes that were really no good for hikers at all. Some of these routes were even illegal for pedestrians to be on.

Fortunately, I was able to change up my route by speaking to Planner Robert Thomas of Pennsylvania, who made some great suggestions that would make my hikes on the route more palpable.

The most recent development was a pending reroute of this trail on the new Essex-Hudson Greenway in New Jersey. The former Greenwood Lake Branch of the Erie Railroad was purchased by the State of New Jersey under Governor Phil Murphy and was planned to be part of this trail.

The problem is, that trail cost $65 million for just nine miles of narrow right of way, which is basically undevelopable, which is well over $300,000 per acre.

That huge payoff goes to Norfolk Southern, the railroad company that more than doubled its campaign contributions to the two governors associations that Murphy chairs and vice chairs. The deal is not allowed through Federal Pay to Play Laws, but when called out on it, the NJ official response was that NJ does not recognize federal pay to play laws.

When I continuously called this out, a friend of ten years who is in charge of these trails blocked me from all social media. No response, no explanation. I was hoping that maybe I misunderstood something about it, but the fact was, it was just as corrupt as I'd assumed.

It seems that many Democrats want to support Murphy no matter what he does, or they cannot accept that their guy is as bad as his Republican predecessor, who pulled a similar deal with rail trails, but for a fraction of the money.

At this point, I had done the entire northern leg from Manhattan to Johnstown. I also wanted to do the entire Great Allegheny Passage as part of it, and so I did all of that from Pittsburgh to Ohiopyle, and I did all of the 911 Trail portion of it from where it joins in Garrett to Cumberland (I still have 35 miles to complete Great Allegheny Passage, where it is not part of the 911 Trail).

So, I had to do from Johnstown to Garrett, which is probably at least three days of walking, and everything east from Cumberland.

I really wanted to get some of the C&O Canal stuff done in warmer months because of all of the swimming opportunities in the Potomac.

The pandemic crap set me behind a lot on the series, and then the fact that they were so far away and would require overnight stays was another thing.

Now, since I've become a father, it seems that all of this canal stuff has come at the perfect time, because it can all be done while my son is still using a stroller.

The stumbling block was that his mother did not want me taking him for an extended trip without her. I kept pestering her about it for months, and she finally told me to just schedule it and she'd decided last minute if she wants to go or not.

This ended up being a hurtful and stressful thing as well, because I found out she planned immediately to go away with another guy to some old hotel to help restore it or something, which really pissed me off because our own home is such a disaster.

Still, I wasn't going to let it ruin this trip. Ev loves doing these hikes, and I felt strongly that it was going to be a great trip for the two of us, and it certainly was.

I had connected to Cumberland before; Jillane and I had backpacked to there a few years back, and we reached both the east end of the Allegheny Passage and west end of the C&O.

I had planned that if Jillane went, we would just do one long day, and then explore around Cumberland the other. If she didn't go, I'd push for two fifteen mile days and connect to the Paw Paw Tunnel, something else I'd been wanting to do for a long while.

Only Joe Millionaire signed up for the first day, but he'd booked his hotel room at the Ramada and was good to go. I was so thankful he signed up because I'd be bumming around the area by myself.

It was definitely an odd feeling. I'm completely on the outs when it comes to the 911 National Memorial Trail people, except for a couple of friends I still have on their board, and hardly anyone is invested in the idea of this series I've been working on. It's just getting too far away for everyone.

With all of this stuff going through my head, and then taking on the long drive to Cumberland alone, and late in the day because Ev's mom held me up again, it seemed like my trip might be doomed.

I drove all the way out, very tired after a long day at work, and found that there was a big festival going on in Cumberland and they had booked my room to someone else, probably because I was so late coming in.

I got my money back, but was worried I wouldn't be able to find a room. I decided I would try the Ramada where Joe Millionaire was, and thankfully they had a room for me.

This was probably better anyway; I had chosen the first hotel room because it was the higher end one for Jillane, and there was a pool and hot tub, indoors, which Ev could use and enjoy, but we were too late to enjoy. The Ramada is right along the railroad tracks, and so when we got the room, and trains would go by regularly, Ev would wake up and go "CHOO CHOO!".

Ev slept great through the night, woke up only once to sip a bottle, and once to say choo choo as a train went by the window.

We woke up to have their continental breakfast. This was different for me, because I'm used to going to get something and bringing it back to the room for Jillane, and more recently, for her and little Ev, but this time I couldn't leave him in the room alone.

I had to get Ev totally ready and bring him down with me to eat, so we basically had to be packed and out of the room before we went down to eat. Since my meeting times for hikes is 9, I milked it to sleep in as long as that time and Ev would allow me.

I cut it a bit close, but we headed down and had good breakfast including waffles, yogurt, cakes, banana, and more. We sat down to eat at a table that the railroad was in view from, and so Ev loved seeing them continue to go by from there.

The active tracks at that point were the former Baltimore and Ohio, the fierce competitor to the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, which amazingly completed to Cumberland before the canal was.

The first canal work on the route was by the Patowmack Company of George Washington himself, which created a series of "skirting canals" around rapids of the Potomac River for navigation purposes.

The original plan was not very successful, and it was realized that a proper still water canal was going to be necessary to open trade to the west. Rejected names for the canal were Potomac Canal and Union Canal. Chesapeake and Ohio Canal was so named for its east and west proposed ends. The canal was to continue westward to connect to the Ohio River and the trade available in its valley.

The first shovel of dirt was turned by President John Quincy Adams on July 4th, 1828. It took until 1850 to reach Cumberland; in those 22 years the canal faced immigrant riots, a cholera epidemic, and a four year legal battle, as well as work stoppages due to financial issues. At 184.5 miles, it only ever reached halfway to the Ohio River. The railroads finished that job, and did so more efficiently.

An 1889 flood caused severe damage and financial trouble, and the canal went into receivership. As such, it fell under the control of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. The canal continued to operate until 1924 when a major flood damaged it and navigation ceased.

The canal was purchased by the federal government in 1938, and some of the lower end was re-watered and opened for recreation. However, in the post World War II years, it was proposed that the canal be made into a parkway similar to the Blue Ridge Parkway and Skyline Drive. The plan gained good support, but the bucolic nature of the canal would be destroyed.

Avid conservationists were already using he old canal for bird watching and walking, and the best ally to the preservation of the canal was Associate Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas.

Douglas asserted "It is a refuge, a place of retreat, a long stretch of quiet and peace at the Capital's back door - a wilderness area where man can be alone with his thoughts, a sanctuary where he can commmune with God and nature, a place not yet marred by the roar of wheels and the sound of horns".

Douglas invited the editors of the Washington Post and Evening Star newspapers to join him on a hike along the canal.

A highly publicized eight day "Douglas Hike" took place in March of 1954, and opinions began to sway in favor of preservation. A sixteen year battle ensued to save the canal, but the idea for a parkway on the route was abandoned. In 1961, President Dwight D. Eisenhower named the canal a National Monument, and it became a National Historic Park in 1971.

The story of Douglas really brings this home for me; it was Douglas who led a hike in what is now Worthington State Forest, for the purpose of saving Sunfish Pond from being turned into a pumped storage facility. A trail on the route he took is named Douglas Trail for him.

My own interest in the C&O Canal goes back to just before I started Kindergarten. I went on a vacation with my grandparents to West Virginia, seeing all the sights, and we stopped for a night in Cumberland (and I think stayed at the Ramada too).

We went to the museum there, and were going to hike the canal, but found out at the museum that it had all been filled in through Cumberland, so we didn't go and try to walk it.

We did however walk by Washington's headquarters and across the bridge over the West Virginia line. I actually remember it pretty clearly, as well as taking a tunnel down beneath the B&O Railroad tracks made for pedestrians.

I had originally planned that we'd walk from Cumberland to the east, and it would be a single two day trip, but I instead made it into two separate hikes with car shuttles, and planned to start from the east and walk west for convenience. It was just the three of us, and we had to manage it with the two cars.

I met Joe Millionaire out in the parking lot by the hotel, and we shuttled in my car from there to our starting point in Oldtown.

Just driving in to this little settlement felt historic. At our first turn onto the main drag, which was the historic old National Road, there were stone remnants of some sort of building that used to sit on the corner.

Where we turned to the right from the National Road to reach the canal, the Michael Cresap House stood at the intersection. The home was built in 1764, and it served as a 1775 meeting point for Cresap and as many as 130 riflemen before marching on Frederick and then on to Boston. The brick addition to the house was built in 1781. The building is considered one of the historic treasures of Western Maryland.

Oldtown, though quite small today, is steeped in history. It was believed to be the site where the Warrior's Path, Athiamiowee, Path of the Armed ones, forded the Potomac.

Others place it further away at McCoys Ferry, but regardless, this was an area that hosted meetings between far separated tribes. Several native American tribes converged here, and in 1715, a group of Shawnee settled here. The settlement became known as King Opessa's Town, for the Shawnee Cheif.

English Pioneer Colonel Thomas Cresap arrived in 1746, at which time the settlement was known as Shawnee Old Town, because by then the Shawnee had left the area.

Cresap acquied the Indian Patent that year known as the Indian Seat and built his fortified home, known as Fort Skipton for his birthplace in England. Nothing remains of that site today.

Cresap was an explorer and trail builder, and served as Commissary to General Braddock when he was heading west to Fort Cumberland.

George Washington stayed at Fort Skipton as a teenager for four nights in 1748 as part of a survey team.

Macadam is named for Scotsman John Loudin McAdam, who is responsible for developing the paving process. McAdam developed roads overseas, and the first US Macadam road was the Boonsboro Turnpike, between Hagerstown and Boonsboro MD.

McAdam's technique involved compacting small stones and material, in an argument that large stones were not needed, and a surface "crust" would provide solid enough base for the roads if kept dry. Centers for roads were three inches higher so water would drain off. His Maryland roads were also the first to be rolled with a steel roller rather than compaction through usage.

The process of Macadam changed a lot over the years, especially with the advent of the automobile. The methods used for carriages no longer worked for how much the cars would kick up. The old style was designed with rocks in mind that would not effect carriage wheels. McAdam told his workers that they could measure the rocks needed by whether or not they could fit inside their mouth!

|

| Steam pump that kept the canal watered |

The use of tar to hold macadam together became more commonplace, and the industry improved.

The National Pike, over the years, became US Route 40. As time went by, larger and better roads overtook or replaced the old National Pike, and through this area came Interstate 68. Some sections of the old road are still now Rt 40, or "alt 40" variations, as well as Rt 144 and byway designations.

During the Civil War, this was also the site of the McCausland-Johnson Raid. The Union Army burned the bridge over the canal in 1764 to keep Confederates under McCausland from taking the fort in Oldtown, but was unsuccessful.

Before heading down, I wanted to try to get something to eat and drink. I was thinking we'd pass more stores on our commute to the start, but there was literally nothing after Cumberland, except for the Oldtown Schoolhouse.

This establishment was quite an oddball one. It was a former high school, which looked like a sprawling layout type like from the 1960s, closed and turned into a deli and store in the former cafeteria. Some of the rest of the place is vehicle repair. It was one of the most odd re-uses for something like this I'd ever seen.

The people running the place were really nice, with thick southern accents. I was glad we found something out there, or we'd have been going a very long way with very little. I just wanted to be sure I had stuff for Ev to eat and drink. It worked out fine.

We headed down over the canal, but first I wanted to have a look at the historic Oldtown Toll Bridge,

Constructed in 1937, the simple low plank bridge is the only privately owned toll bridge in Maryland, and the only one over the Potomac River, just below C&O Canal Lock 70.

We parked in the lot on the canal adjacent to Lock 70. Locks 69 through 71 are the three Oldtown Locks. These ones are described as "economy locks" because they were constructed of composite stone, on which kyanized wood planking would be placed to keep boats from damaging the walls. These composite stone locks are the ones we mostly saw on the Delaware and Hudson Canal, with the fine cut stuff only in certain areas.

The three locks were built in 1849-50, and in later years were outfitted with concrete to replace the original wooden planking inside, which is similar to what was done on some of the Lehigh Canal we'd seen.

Lock 70 was the central lock in Oldtown, and a center for commerce. A store once stood behind the lock house, which is still there, though not the original one. In 1850, a pivoting bridge was built over the canal here, which allowed for passage of boats, but it burned in 1906 taking the canal store and lock house with it, so the one we see today is likely built in 1906. The bridge was replaced by a steel truss structure, which was eventually replaced by the one there today.

There was also barn building on the north side of the canal, and a large wharf in a wide section to the west.

We walked up from the parking area and over a foot bridge across the middle of the lock to the towpath.

This was my first time seeing a C&O Canal lock, and my first impression was that this had been a double lock for opposing traffic, but that assumption was wrong.

The secondary channel I was seeing was a bypass flume for the water going around the lock. Most locks have these in place, but this one was very uniform. In fact, almost all of the locks we saw on this trip had a very similar lock layout, with a substantial bypass flume built into a larger superstructure. Most of the bypass flumes I'd seen on other canals were deteriorated pretty badly, or if they weren't, they were all sort of oddball configurations that worked along with the limitations and advantages of the terrain around it.

We turned right to head west on the canal right away, and I let Ev walk for a while. It's slower going with him when he's walking, but he moves along at a better pace all the time.

I just had to watch him along the locks a bit because it's a big drop. Overall, I don't have to worry about him too much on these things because he's kind of afraid of the heights enough that he won't go too close to the sides.

This entire section of the canal is in fine shape and watered. In 1957, Oldtown Sportsmen Club did much improvement to this section to use the canal as a fishing pond. The area was designated Battie Mixon Fishing Area in honor of the member of the sportsmans association that started the project to restore.

We continued ahead as the canal follows the bed of the Mill Run, previously known as Big Spring Run, which is now on the north side of the canal in its own channel. Just ahead was Lock 71.

Very similar to 70, this one had the bypass flume to the right as we approached and a foot bridge over the lock channel. The lock house here is also still standing, and serves as National Park Service storage.

We continued above the lock, with no shade at all at first. It was the only bad thing about this first section on a hot day. Fortunately, I had my guide book that told us that we'd soon be in shade.

For this trip, I have the Towpath Guide to the C&O Canal by Thomas F. Hahn. Hahn wrote the book using the mileages and notes of Orville Wright Crowder, who walked the entire canal between 1957 and 1959 pushing a surveyor's wheel for accurate mileages. Crowder was an accomplished hiker and climber, and was the third person to ever hike the entire Appalachian Trail. Hahn followed Crowder's mileages and brief notes, did his own further research, and wrote the book, which has been updated numerous times. Hahn died in 2007, but the book has been updated accordingly and is a great reference guide.

A little past lock 71 was supposed to have been the site of the James Cresap Mill. A bridge had been erected over the canal to serve the mill in the past, but we saw no remnants of a bridge or a mill site while walking by here.

I watched closely for everything of interest along the way, and I did notice what looked like a concrete waste weir to the Mill Run off to the right across the canal.

Pretty soon, we left the area of watered canal and continued into woods, at the start of a cut. I didn't think too much of it at first, but this cut soon became incredibly impressive.

This was known as the Alum Hill Deep Cut. We soon found ourselves in a deep chasm carved for the canal with sheer walls of shale rising up on both sides. It is believed that the canal might have utilized an earlier channel of Big Spring Run to pass through this big cut.

We could reach down and put our hands into this shale, and pick it out in long pieces that looked like knives.

This must have been a nightmare for maintenance, because we could rip these walls apart with our hands. It must have closed in on the canal regularly, and even today, to keep the towpath open through the cut must be tough.

We came out of the cut and continued; the Potomac River came close to us on the left.

Ahead, we came to a large basin on the right. Joe Millionaire pointed out that the end of this basin was an odd slope of black and brown dirts, which at the time we just figured was some geological phenomenon from the ridges that come down to the river there.

As it turns out, we were looking at the fill that carried the Western Maryland Railroad over the basin.

Much of this section of the Western Maryland Railroad, a direct competitor to the Baltimore and Ohio, was constructed in 1904 to Cumberland, and was just another thing in the way of the C&O traffic.

We continued on with fields and such parallel with the canal. Ahead, we passed the Pigman's Ferry Hiker/Biker campsite. When I was first planning to do hikes on this, I was hoping to camp at this site.

Thee was a culvert that carried a stream beneath the canal just before the campsite, and a water pump right there along the trail. I believe this first one I could not get pumping water, but they all pretty much work.

Somewhere in this area, Confederate calvary under General John Imboden cut the canal in this area causing major erosion damage.

This and the area railroad bridges his men burned screened General Robert E Lee and allowed his advancement through Maryland, which ultimately led to the bloody battle at Gettysburg.

Somewhere in this area also was the former site of the Shelhorn Tavern, which was in operation in 1795, but I saw no remnants.

The canal came closer to the river again, in a narrow area with rock folds on the berm side and some nice views to the river. Through this stretch, there were several culverts that carried streams beneath the canal.

We passed by a dry former basin that was known as the "Basin at Alkyre's House", but no remnants of anything else there.

We were moving along really at a good speed at this time. I put Ev in the stroller, and he was happy to be in there for a while, so we were really moving along. Route 51 came close to the right of the canal, and so we could somewhat hear cars for a while, but it was really never a feeling of being in a developed area. We also passed Spring Gap Campground, which is one that can be driven up to. There were always cyclists going by, and occasional walkers, but still not all that many for a beautiful Sunday.

For a while, we were immediately parallel with the Western Maryland Railroad bed, but that disappeared and came back along the way.

As we continued, we passed the abutment to an old bridge on the left, which was made of an odd jigsaw style pattern of stones rather than straight in-line stone work. There must be some structural advantage to having built something so much more complicated.

The next point of interest was the site of the old canal water supply pumps. It looked like a flume going off to the left of the towpath, to a foundation structure closer to the river.

A centrifugal steam pump had been placed at this location in 1875 to pump water up from the river and into the canal via the long flume. It was reported to have brought 24 cubic feet of water per second into the canal. This replaced an earlier pump system that had been placed at Lock 68 in 1856.

We continued ahead and crossed a nice waste weir, then I missed a side trail to Blue Hole, one of the largest springs in Maryland.

There's so much stuff to see in this area, I could probably do it over and over and still find something new. Surely, if I lived closer, I would.

Soon, we came upon Lock 72, also known as the Ten Mile Lock, because it was about ten miles from here to Cumberland. It is the start of what in canal days was known as "The Narrows", because the canal is squeezed into a tight space between the Potomac, Nicholas Ridge, and Irons Mountain.

Lock 72, which lifted boats nine feet, was made of fine cut stone quarried from nearby. It was built in 1841. The lock house here is still standing in pretty good condition.

The Douglas Hike in 1954 started at this location because the canal to the west of here was in such bad shape, and through Cumberland is pretty much obliterated.

We continued ahead from here through the narrows, and soon reached the first of the North Branch locks, the final three lift locks on the canal before Cumberland. Each of these three locks was constructed of fine cut stone taken from the Evitts Creek Quarry nearby.

Lock 73, which lifted boats 9 feet, was constructed in 1840 and rebuilt in 1869. The Irons Mountain campsite was immediately next to the lock on a slope down from the canal, with a pathway from there down to the Potomac River. This was a great opportunity for a dip.

We headed down, and as we descended saw a train going across the nearby CSX railroad bridge. I went down the steep slope and got in the river to cool off, which was great, while Joe Millionaire waited up top with Ev. I got a video of a train going across the bridge, which made Ev very happy to see.

This was originally the Baltimore and Ohio crossing site, with the original bridge built in 1842. It was replaced by a steel bridge in 1923, and by the one standing there today around 2015 as I understand.

I didn't take long, just enough time to cool off, and came back up to Ev. I told Joe Millionaire he should really head down and enjoy the dip himself, and he went for it. This was just a great little spot for a break, and I also had some water from the pump.

We came back up to the canal and continued walking. Ev went barefoot for a little bit here. We soon passed beneath the former Baltimore and Ohio line, which had a train parked on top of it at this point.

We continued ahead, and soon reached Lock 74. This lock, completed in 1841 and rebuilt in 1869, lifted boats 10 feet. These locks had drop gates installed to replace the old miter gates at the upper ends probably around 1875. Unfortunately, the lock house at this location burned in 1974.

Just after lock 74, we reached Lock 75, the final lift lock on the entire canal, which lifted boats 10 feet. This was 609.193 feet above the tide lock at the eastern terminus of the canal in Georgetown.

The lock, like the previous two, were reconstructed in 1869 of fine cut grey limestone. The log lockhouse at this site was reconstructed in 1978 to historic specifications, and lower lock doors were also put back in place.

Less than a mile ahead, we reached and crossed River Road. There was an industrial complex to the left, the North Branch Pumping Station (formerly Pittsburgh Plate Glass). We crossed River Road, and then skirted fields to the east. To the left, there was a mowed side trail we decided to explore, which was to the iron gated Pollock Cemetery, where Confederate soldier James D. Pollock is buried. A farmstead was just to the south of this location, which looked abandoned. We returned the same way we got there, with views of Knobley Mountain near Cumberland ahead. This area was the approximate location of Van Metre's Ferry.

We continued ahead, and the canal swung out along farmlands that were quite pleasant.

The area we passed through ahead was known as Mexico Farms. In this area was one of the nation's oldest airports, established in 1923. Prior to that, a native American village once existed on this section of level land along the Potomac.

We crossed over Mexico Farms Road, and at this point, an abutment was still in place from where the Western Maryland Railroad used to cross over the canal and road.

The canal at this point was coming much closer to developed areas, and I was expecting an area of little shade and lots of buildings, but it was not like that at all. All of this remained quite wooded in feeling at least.

We crossed Canal Road, followed by Brehm Road, where there were actually some houses along the path. The latter road once led to Kirkendall Ferry over the Potomac.

Ahead, we crossed over a nice combination waste weir and culvert unlike others we had seen. Part of me regrets now going down to look at all of the historic culverts, but there were just so many of them and we had to keep moving along.

Pretty soon, we reached Evitt's Creek campsite, the last campsite when heading to Cumberland.

We continued westbound, and pretty soon reached the Evitt's Creek Aqueduct, a 70 foot single stone arch completed in 1840. Stabilization work was done by National Park Service in 1979 and 1983. Other culverts take Evitt's Creek beneath adjacent railroad yard and Rt 51.

We took a little side trip down by this aqueduct to have a look at it from below, and I took another dip on the creek to cool off.

Although this is the smallest of the arch aqueducts, it is quite impressive. No water flows through today, and we had the choice of either walking down in the water trough, or on the towpath.

We soon reached the Cumberland City Line, but the canal didn't become very developed in nature.

We did pass the Cumberland Wastewater Treatment plant, and then reached Candoc Recreation Area, which is sort of an Acronyn for "C AND O C(anal)". We continued past this, and there was a spot where the canal and towpath appeared regularly mowed, although dry.

Soon, we passed beneath the abandoned Western Maryland Railroad again, which crosses on a through girder bridge. I had Joe Millionaire stay with Ev for a moment while I climbed up the bridge to have a look at the right of way.

I walked toward the Potomac a bit, hoping that maybe it'd be clear enough to get a view of the abandoned trestle it uses to cross, but it was very overgrown and would have been a serious push to get to that site.

As soon as it crosses the river, it entered the Welton Tunnel, which goes directly beneath the Cumberland area airport on the West Virginia side. I've been told that the tunnel is collapsed about midway through.

In this area was the former site of Wiley Ford, where travelers forded the Potomac River. Just past the original site is the Wiley Ford Canal Bridge, which carries Airport Parkway, Rt 61, to the airport.

It wasn't far beyond this point that we came to another former crossing of the Western Maryland Railroad. Here, there is a side path up to it, and it is the Carpendale Rail Trail into West Virginia.

The bridge that carried it over the Potomac again here has been well decked. We decided to take this side path, which was quite lovely. Once we got to the other side of the bridge, the railroad immediately entered Knobley Tunnel.

I was hoping to take a side trip through the 1904 Knobley Tunnel, but it was fenced off on the east side because there was apparently a bad collapse closer to the west side. At least we got to see it, and we headed back the way we came across the bridge and back down to the canal towpath.

In this area, in the middle of the night, February 1865, a unit of Confederate soldiers known as McNeill's Ranges slipped into Cumberland in the middle of the night and surprised two Union generals in two different hotels. Major General Benjamin F. Kelley and Major General George C. Crook were ordered to dress and taken by horseback, using part of the canal towpath toward Wiley's Ford, before 7,000 Union troops knew what had happened. Both Generals were taken to Richmond and treated well in captivity until exchanged a month later.

We walked along the towpath through an area where the railroad was above us to the right.

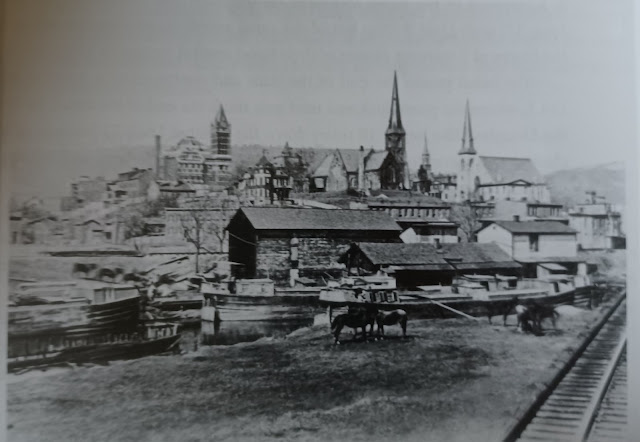

Pretty soon, we reached where the route opened up to an unobscured and quite amazing view of Cumberland. Gone was all of the shade we had walked in, and I was beyond amazed that the canal remained through the city to this point without really ever giving indication that we were coming to an urbanized area.

The area was radically altered in 1959 as part of a flood control project. The canal trace was eliminated, and a large berm is where the trail follows today. Beyond the cityscape we could see the Wills Creek Narrows in the mountains beyond.

There was an 1849 set of piers from a stop gate that kept the Cumberland Basins full of water when the rest of the canal was drained for Winter maintenance. Dredges and scows were kept in this area for work, and boats could be stored.

We continued along the path toward town, and we came to the remaining abutment of Dam #8, which was the last of the water supply dams to provide water for the canal. The dam was 400 feet long and 17 feet high. It was blown up by the Army Corps of Engineers in 1958 at the start of the flood control project.

Just ahead of the former dam, we came to the outlet lock, where we could still see gate pockets in the sides of the walls below the railroad bridges in the area today. These locks were used as solid footing for many of these rail crossings.

A basin stretched a bit further north from this point, and there is a marking in the walkway in town placed to denote the end of the towpath and navigation near the Western Maryland Railroad station.

Cumberland was established as a town in 1787, but was the site of Fort Cumberland before that, and has a great amount of history to be explored, which I've detailed in previous hike journals where we reached the point.

We cut across from the outlet locks on one of the rail bridges, which had a good walkway on the side, to the platform of the Western Maryland Railroad station, which is always a sight to see.

The beautiful station was built in 1913. The Western Maryland reached Cumberland about 1904, but this station was built just after the completion of the Connellsville Extesion in 1912.

While what we had been walking along has been abandoned for quite some time, to the west of Cumberland, the former Western Maryland is used for excursions, and the trail runs beside the tracks all the way to Frostburg. To the west of there, it is abandoned the remainder of the way to Connellsville, and it was made part of the Great Allegheny Passage Trail in 2006.

We stepped off of the platform at the front of the station and turned right on Baltimore Street.

We went someplace for dinner in the city, but I can't remember for the life of me where it was. I remember Joe Millionaire looked it up and we made a few turns, then had a really nice outdoor seating spot. The burger was really good. But I don't know what place it was.

From there, we simply walked a few blocks to the Ramada and Joe Millionaire's car, and he got us back to Oldtown. Ev and I rode back to the Fairfield Inn and Suites, because they hadn't screwed up this night at least.

We went for a dip in the pool, and had a good relaxing night in the room. Ev fell asleep on the bed next to me pretty easily after the long day, and I couldn't wait for the next one. Despite all of the silly drama that led up to this, nothing was going to ruin it for us.

No comments:

Post a Comment